Before we moved to the Western Slope, we were told again and again to make sure we buy water, not just a farm. Over here, water and land are sold separately, like toys and batteries. Just because water runs through, on or over your property doesn’t necessarily mean you have any right to use it.

The good news is that Quiet Farm does have adequate water, in most years. The bad news, however, is twofold: first, the Western Slope is in an unprecedented drought and at the moment no one has enough water. And second, we know precisely nothing about irrigation management. When you live in modern suburbia you just turn on the tap and the water flows magically, right? That is so much not the case here.

Irrigation management on Quiet Farm doesn’t look like this.

It looks like this: our Parshall flume (or weir) with attached flow gauge. No, we don’t know what any of those words mean, either.

This is our water pump with screen to catch wildlife – raccoons, ground squirrels, marmots, whistlepigs, ponies, etc. – when they fall in. Looking forward to THAT happening.

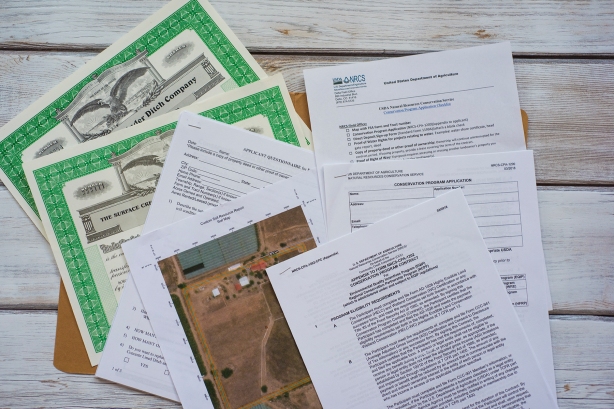

We now own two shares of one of the Western Slope’s strongest irrigation ditches. There are dozens of ditch and reservoir companies; the vast majority of the area’s water comes from hundreds of lakes and reservoirs up on the Grand Mesa which are filled with precipitation each winter. When there is no snow, like last year, then there is no water in the ditches or reservoirs. And so water becomes a very valuable commodity.

This is known as an “ag tap,” an abbreviation for agricultural. The water from this tap, however, is from our domestic supply. Confused? So are we.

This is downstream of the water pump and will help irrigate our land with irrigation water. We think. Or maybe not.

When we want some of our water for irrigation – which we can have between the beginning of April and the end of October – we order a precise amount from the ditch company, accounting for absorption and loss along the way. Ditch riders, who live up on the mesa during the season, use a complicated system to send the water down the correct ditch to our property on a specific day. We have to be out at our headgates at about 6AM to start our run, and the water we use is debited from our account, just like a bank. We can lease, sell, trade or give away our water as we see fit, but if we order water, it’s coming to our property whether we’re ready or not. So figuring out our irrigation system is of paramount importance to our future success.

Our water will run through gated pipe, a common sight in our area. Big farms will own thousands of feet and it’s set up according to your property’s individual landscape and contour. The black gates open and shut to control the water flow.

A lot of our gated pipe currently looks like this, which is obviously not workable. Even we know that.

In case you’re worried that we’re actually living in Little House on the Prairie, our house has a domestic tap, which is just like water in a normal house. Except that domestic water here is crushingly expensive, especially compared to Front Range rates, which means we absolutely cannot run a farm on domestic water without bankrupting ourselves. No more domestic taps are being issued in our area; local government doesn’t think we have the water to support additional growth – unlike on the Front Range, where greedy, short-sighted counties sell their water to the big cities and then wonder why their towns die. Domestic taps are worth tens of thousands of dollars over here, if you could even buy one.

Apparently little critters like chewing on the gates inside the pipe. The gates cost $3 each, and we have dozens missing. The few remaining intact ones are probably being eaten right now while you’re reading this.

The end of the line. Of course, if the pipes aren’t connected properly we’ll just flood everything and there is no way to turn the water off once we’ve called for it. So good luck with that.

We’ve got just about a month to figure this system out, because once the water goes off at the end of October we’ll have no way of testing our work. And when the water (hopefully) starts running again next spring, we want to be ready to get our pasture in good shape.

Good news, though! We’re unknowingly growing a pasture of invasive elm trees that will need to be removed by hand…

…when we’re not growing anything at all. Surprisingly, bare pasture is actually worse than having even invasive plants in the ground.

The moral of this tale, friends, is not to take water for granted. The daily luxury of fresh, clean, potable water is an absolute gift and one that not even everyone in the U.S. has access to. So treat your water like the precious resource it is, and know that it is finite. And wars over water will be much more devastating than wars over oil.

There is much work to be done, and winter is coming. Pray for snow.