(Forgive our extended absence, friends; we’re in rural India and Internet access is sporadic at best, and we need a really strong connection to upload photos. How about a suggested reading list to keep you busy until we return?)

Prior to a five-month trip, some people might well worry about how many pairs of shoes they can bring, or whether their hairdryer will fit in their backpack. Me? I stress about books.

I am aware, dear reader, that there apparently exist magical devices powered entirely by witchcraft that allow one to carry dozens – nay, thousands! – of books on a tiny little computer. I, however, am an avowed Luddite and therefore refuse to succumb to the temptation of this modern silliness. I like books. Actual books. I like paper and covers and words printed on a page and I find e-readers inordinately difficult to, well, read. And I love reading so much that I don’t want anything to detract from my enjoyment. Plus, traveling in underdeveloped countries means on-demand electricity isn’t always a given, so what am I supposed to read once my e-reader fails? At least I have a battery-powered flashlight with which to read my paper books. And a lighter after that, although it’s admittedly a bit risky.

So, I pack books. Lots of books…like ten, which takes up a seriously ridiculous amount of space in my backpack. And I pack with the expectation that those ten will maybe set me up for the first couple of months of travel but I’ll certainly be able to swap books out along the way…if in fact there is anyone else in the world who still reads books on paper. When we traveled New Zealand by campervan, I was thrilled to find that almost every campground we visited had a great book swap.

This photo was taken in a used book store in Phnom Penh and not in our house, although the quantity isn’t far off. Also I haven’t labeled the shelves…yet.

In preparation for the trip, I scoured the hundreds of books I have at home to find some that were in some way relevant to where we’d be traveling. I read mainly modern fiction, but am pretty open-minded in my literary tastes and will read just about anything that crosses my path. I grabbed a couple on Japan, couldn’t find anything set in New Zealand, struggled with southeast Asia, and hit the mother lode with India. India-themed fiction has become quite popular in the past twenty years or so, and I already owned a good sampling.

Without further ado and in no particular order, brief reviews of the selections chosen for my ongoing one-member Indian book club!

Shantaram, Gregory David Roberts

This book had been recommended to me repeatedly for years, and though it’s been on my bookshelf for some time I never got around to reading it. I grabbed it for this trip and am so glad I did. Shantaram is lengthy and twisty and convoluted and involves about ten thousand different characters, and yet the story grabs your heart and won’t let go. Bombay (now Mumbai) is its own vivid character in this book, and although Shantaram‘s claim as an accurate autobiography (is there such a thing?) has been repeatedly disputed, it absolutely holds up as a novel. I’m still thinking about this one months later, especially since we visited some of the book’s key locales while in Mumbai.

What Young India Wants, Chetan Bhagat

An unexpected find at a book exchange at our Mumbai hotel and by far the best book I read on India while in India. This book is intentionally simplistic: it’s a collection of very short non-fiction pieces by an Indian author who is essentially begging the youth of India to stand up and care about their country. India is without question the most complicated, difficult place I’ve ever traveled, and I’ll admit that I was often infuriated here. This book helped me to understand some of the country’s issues better, and I can only hope that young Indians are paying attention.

The Case of the Man Who Died Laughing, Tarquin Hall

Light, fluffy Indian detective fiction, in the vein of The Number One Ladies’ Detective Agency series. This is gentle social satire and although perhaps not particularly insightful, it gives a good feel for the scents, sights and – most importantly – the unrelenting heat of Delhi.

The God of Small Things, Arundhati Roy

There is nothing light and fluffy about this book. It is a stunning debut novel that took the author four years to finish, and it’s dense, layered, challenging and brutal. It won the Booker Prize…in my opinion, that committee loves books like this. Not an easy read; this one is firmly in the difficult-but-beautiful category.

The White Tiger, Aravind Adiga

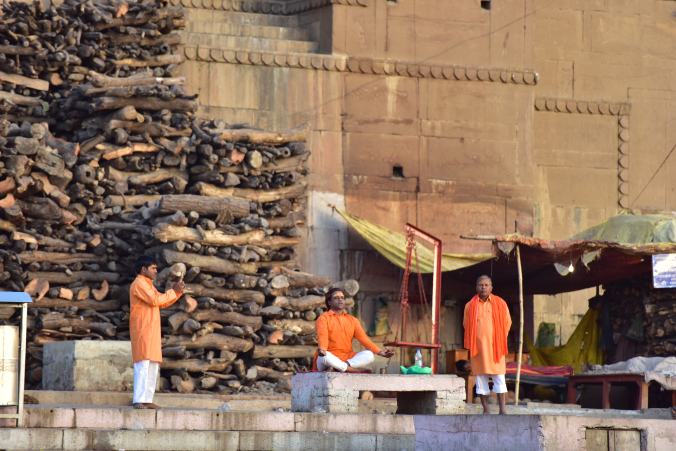

Also a Booker Prize winner. I read this towards the end of our first week in India on a lengthy bus/train trip between Darjeeling and Varanasi, deep in the throes of severe culture shock. While the book’s first-person depiction of the sordid underbelly of India’s servant-to-master relationship intrigued me, I couldn’t get past the infuriating, hopeless, complicated frustrations of the country – mostly because we were experiencing them in real life one after another. And that was because I hadn’t yet learned how to see India for India, rather than what I expected India to be. I suspect if I read this book again, I’ll have a different opinion.

The Space Between Us, Thrity Umrigar

This is the story of two Indian women: a middle-class Parsi in an abusive marriage and her servant, who lives in a slum. At its heart, it’s a tale of class and status and the roles we’re born into, but it’s also about how women are treated as disposable property in much of the world (most definitely in India). I should have loved it, honestly, but it left me completely cold. I didn’t care about the characters and found the overwrought writing tedious. This book definitely didn’t represent the color and warmth of India for me.

Midnight’s Children, Salman Rushdie

In the U.S., at least, Rushdie is most famous for his controversial 1988 book The Satanic Verses and for introducing Americans to the concept of fatwa, which in his case was a Khomeini-issued death sentence that earned him British police protection after numerous failed assassination attempts. Midnight’s Children was released in 1981 and won Best of the Booker twice, which is pretty remarkable. Like all Booker Prize winners I’ve read (see above – maybe the committee really likes books set in India?), this one is complex and messy and confusing – like India itself – and just a huge, broad tale of a man and his beloved country. Midnight’s Children is considered magical realism, and Rushdie’s writing style took a bit for me to get into – I had to work at this one more than I usually do when reading. (It would help greatly to have a working knowledge of Indian history since Partition to assist in reading this book; I didn’t and it was more difficult because of that.) Ultimately, a complicated love letter to a complicated country.

Atlas Shrugged, Ayn Rand

Not Indian-themed, obviously, but I’ve read it numerous times and have taken – and given away – copies on all of my big trips. If you’re reading this in an airport or other public venue, I can almost guarantee you’ll be approached by someone who wants to discuss it, which has happened to me on more than one occasion. Really, there isn’t anything else to say about this one that hasn’t already been said. It is a love-it-or-hate-it manifesto and it’s about a thousand pages. Please don’t cheat and watch the film.

On the to-read list for when we return: The Things They Carried and A Rumor of War. I’ve realized how little I know about the Vietnam War, and visiting Vietnam has made me exceptionally curious to learn more.

Have any book recommendations? I would love to hear them, so please share!

P.S. If you’re an avid reader (and live in the U.S. – sorry) and you’re not a member of this site? Get there now.