With the intense heat and the wildfire smoke, we’ve been spending more time than normal indoors lately. This is terrible news for our climate, but good news for our reading lists! This round-up is heavily weighted towards non-fiction (with a clear attention economy/stolen focus bent!), but I have a couple of dark suspense novels lined up (Lisa Jewell’s None of This Is True and Lucy Foley’s The Paris Apartment) to carry me through these dog days and into (hopefully) cooler temperatures. (You can check out a few previous book review posts here, here and here.)

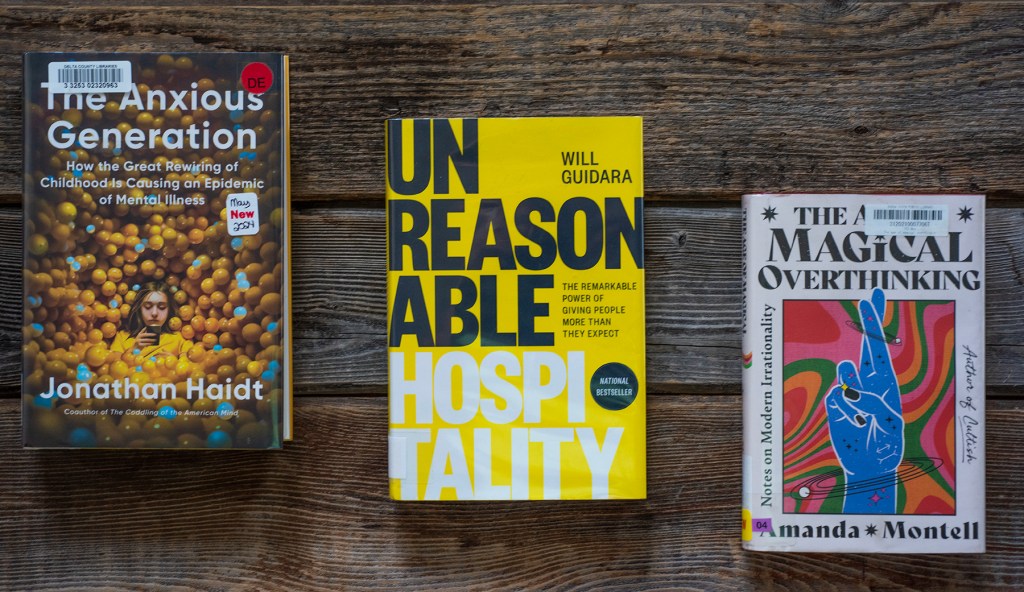

The Anxious Generation, Jonathan Haidt

Jonathan Haidt’s new book, subtitled How the Great Rewiring of Childhood is Causing an Epidemic of Mental Illness, has gotten a ton of both positive and negative press recently. The book’s essential thesis is that we’ve moved from a play-based childhood to a phone-based childhood, much to society’s detriment. Parents overprotect their children in the real world – no playing outside in the front yard on your own because you might be kidnapped! – whilst at the same time handing them a smartphone with unrestricted access to all of the horrors humans can dream up. He also argues that social media in particular has contributed to (caused?) most of the dramatic increases in depression, anxiety, eating disorders, suicidal ideation and more mental health issues seen in pre-teens and teenagers in the Anglosphere.

It’s tough to disagree with this book’s basic premise about limiting our kids’ excessive technology access for their own sake (and society at large). Just about everyone knows that we’ve willingly surrendered everything to Big Tech’s darkest, greediest impulses, and that we threw our children into the sacrificial cauldron of 24/7 internet access, image sharing, influencers and data harvesting without a second thought. At the same time, many researchers have taken issue with Haidt’s data selection, suggesting that meta-analyses don’t show the results he claims. As always in science, correlation is not causation.

The book smartly proposes more free play and autonomy for kids, and suggests that children not be given smartphones until at least eighth grade, not be allowed access to any social media accounts until they’re sixteen, and that phones and devices be banned in schools entirely. Most any reasonable adult would agree with all of these suggestions in theory – but they’ll never be put in place: in order to address screen addiction in children, we’d have to address it in adults first and that simply won’t happen. Secondly, attributing mental illness to screens in general and smartphones in particular doesn’t acknowledge the myriad policy mistakes and the systemic change needed in order to truly transform society. Instead of parents wanting children to have phones in case of a school shooting, why don’t we talk about guns? Instead of virtual tweets against Big Oil, why don’t we actually tackle the climate crisis? Instead of crying over our deteriorating mental health, why don’t we make health care affordable and accessible?

Overall, the book is a worthwhile and important read, with plenty of sobering statistics. I particularly liked the concept of “antifragility” as it relates to both our psyches and our immune systems: just as a healthy immune system requires regular exposure to dirt, bacteria and other threats, it follows that insulating our kids from all challenges and inconveniences produce anxious young adults with zero resilience. Perhaps someday soon social media will be as vilified as smoking, with only a small percentage of the population choosing the clearly negative health outcomes. I don’t think this will happen, though – and worrying about kids’ smartphone use now is a very clear example of closing the barn door after all the horses have long since bolted. We voluntarily gave ourselves over to Big Tech, and we are too far gone for any real change to occur. Wringing our hands now doesn’t do much at all.

Unreasonable Hospitality, Will Guidara

Prior to launching the farm, I spent most of my career (such as it was) in F&B and hospitality, so it’s no surprise that I loved Will Guidara’s Unreasonable Hospitality. (Guidara came up under Danny Meyer, another hospitality legend; I also highly recommend Meyer’s seminal Setting the Table.) On the surface, it’s merely a book about Guidara and his business partner-chef, Daniel Humm, turning a perfectly fine three-star restaurant into the best restaurant in the entire world, but at its core, it’s one of the best business books I’ve ever read. Much like Bob Iger’s Ride of a Lifetime, another of my very favorite business books, Unreasonable Hospitality isn’t so much about running a top restaurant (or overhauling Disney) as it is about providing more than what’s expected, taking excellent care of your team and always striving for incremental improvement in whatever task or skill you might be tackling. The book’s lessons aren’t particularly revolutionary or groundbreaking, but they remain essential to running a decent company, no matter the industry; these human-focused ideas will become even more relevant as we move more and more into automation in all areas. I loved the quote from Guidara’s father, also a hospitality professional: “Adversity is a terrible thing to waste,” meaning that people and businesses build resilience and often thrive in seemingly terrible situations (see also: the pandemic). Unreasonable Hospitality is wholeheartedly recommended for anyone who works with people.

The Age of Magical Overthinking, Amanda Montell

“How are we living in the Information Age – and yet life seems to make less sense than ever?” Amanda Montell’s third book is a “sweeping look at mental health, behavioral science, misinformation, and online culture in the 2020s.” Each chapter follows a specific cognitive bias, such as the sunk cost fallacy, zero-sum bias, confirmation bias and more. She argues that “our brains are overloaded with a constant stream of information that stokes our innate tendencies to believe conspiracy theories and mysticism.” Cognitive biases developed to help us reconcile our limited time, memory storage and cognitive resources; we honed these shortcuts unconsciously to help us make enough sense of our environment to survive. Now, however, survival is mostly a given – but our brains haven’t caught up, and Big Tech is heavily exploiting these same tendencies in the race to the bottom. Cognitive biases are at least partially responsible for the pervasive spread of misinformation and disinformation, especially online; once again, our nonstop addiction to our devices (and an unrelenting firehose of questionable content) is fueling this general sense of anxiety, unease and panic.

Overall, the book comes across as a disjointed mess. It purports to be “a delicious blend of cultural anaylsis and personal narrative,” but that brush is far too broad and the chapters lack a sense of connectivity. Montell neither proves nor defends her hypotheses with any vigor, and the book often feels off-balance with too much memoir and not enough science. The Age of Magical Overthinking is an ultimately shallow summary of some vague social and/or psychological science and how that might relate to our modern world, with quite a bit of Taylor Swift and other sparkly pop culture figures sprinkled on top to maintain interest. The reader is frequently left wondering whether the author understood the topic well enough to actually write a book about it.

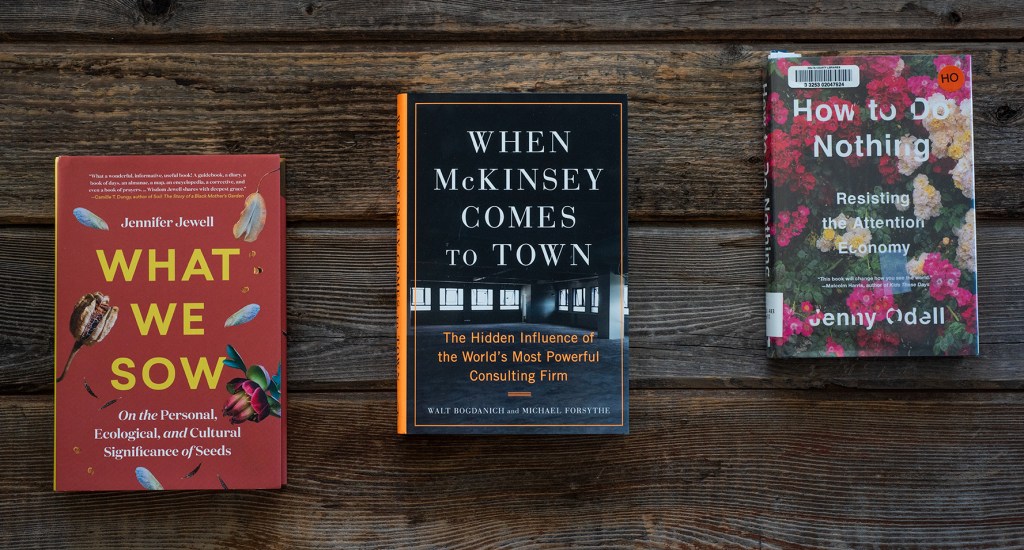

What We Sow, Jennifer Jewell

I am precisely the target audience for this book, and as such it is no surprise that I loved it. What We Sow is part memoir, part gardening journal, part seed manual, part botany lesson and part meditation on the natural world, and Jewell does a beautiful job of tying these threads together. Jewell began the book in the spring of 2020, when just about the entire country collectively decided to start gardening; this of course resulted in disruptions in seed supply and a renewed interest in the collecting and saving of seeds (one of my great passions). Jewell writes, “In this bizarre moment of colliding urgencies for life as we have known it, we are collectively being offered an opportunity to remember and really understand the essential importance and power of seed in our world: for food, for medicine, for utility, for the vast interconnected web we include in the concept of biodiversity and planetary health, for beauty and for culture, whatever that might mean to us.” Seeds are life, and learning about seeds and seed saving is one of the single most important things we can do in our ever-more-fraught battle against climate collapse. Highly recommended for any gardeners and farmers.

When McKinsey Comes to Town, Walt Bogdanich and Michael Forsythe

“One former McKinsey consultant wrote anonymously, ‘To those convinced that a secretive cabal controls the world, the usual suspects are Illuminati, Lizard People, or ´globalists.’ They are wrong, naturally. There is no secret society shaping every major decision and determining the direction of human history. There is, however, McKinsey & Company.'”

The name McKinsey & Co. might not necessarily be familiar to you, but you know their work – and not in a good way. Think of any major illicit, shady, morally corrupt or even vaguely unethical organization, industry or practice around the world – opioids, insurance, despots, the U.S. government – and it’s highly likely that McKinsey & Co.’s greasy fingerprints are all over it. They’re merely the world’s most powerful consulting company, and their mandate is usually fairly simple: a company (or government, or the NHS) enlists McKinsey’s services to cut costs and improve shareholder returns. Unsurprisingly, this often means sacrificing employees, customer service, the environment and/or safety. What is surprising is how remarkably banal their work is – mostly uninspired PowerPoint slides reading “deny, delay and don’t pay” that AllState spent millions to keep hidden.

Conflicts of interest are rampant (advising both the FDA and Big Pharma at the same time?): in an extraordinary settlement, “McKinsey & Company, the consultant to blue-chip corporations and governments around the world, has agreed to pay nearly $600 million to settle investigations into its role in helping “turbocharge opioid” sales, a rare instance of it being held publicly accountable for its work with clients.” Despite this settlement, their work, at least as presented in this book, is certainly morally questionable but likely not technically illegal. McKinsey simply cannot be blamed for all of the ills of modern capitalism, much as it would be nice to identify a ideal scapegoat. Much of the time, they provide the perfect excuse to move forward with cost-cutting measures that companies already want, a kind of expensive rubber stamp. Their work with despotic governments (China, Saudi Arabia) is given the side-eye here, but there isn’t much reflection on the hundreds of millions they earn from the U.S. government (not exactly a paragon of virtue). Plus, as McKinsey themselves point out more than once, if they didn’t do this work, someone else certainly would – and that’s not untrue.

This book is shocking, but not surprising – really, it’s more of a how-to manual for How America Does Business. And if you’re curious as to whether you, personally, have ever been screwed by a McKinsey client, the answer is definitely yes. When McKinsey Comes to Town is a terrifying horror story – except that it’s non-fiction. And (mostly) legal.

How to Do Nothing, Jenny Odell

“There are more reasons to deepen attention than simply resisting the attention economy. These reasons have to do with the very real ways in which attention – what we pay attention to and what we do not – renders our reality in a very serious sense.”

How to Do Nothing was not at all what I expected, and I liked it more for that reason. The title might be construed as somewhat misleading (subtitle: Resisting the Attention Economy) and many reviewers mentioned that they expected more of a traditional how-to self-help book on digital detoxing. It’s true that How to Do Nothing doesn’t exactly know what it wants to be, but I think this is a feature rather than a bug, as it requires more effort on the reader’s part. Odell presents a thoughtful and well-researched work on what we lose when our phones and the 24/7 news cycle do not allow us any time to process, analyze and think carefully and critically about anything we encounter. Interestingly, How to Do Nothing was written prior to the pandemic; I’d argue that we’re all far more addicted to our phones and technology now than we were in 2019.

A valid criticism of the book is that it definitely contains abstract and somewhat esoteric thought lines and is exceptionally meandering at times (this one-line review made me laugh: “Woman discovers trees and writes about it in the language the rest of us use for grant proposals.”) Portions of the book are written in dense, murky academic prose and are almost incomprehensible. Despite its unnecessarily lofty style, How to Do Nothing forces some hard questions – what have we lost while on our phones? Odell would say our relationship to nature, to each other and to ourselves. We do not owe anything to the attention economy and it is destroying our last vestiges of humanity, but the ultimate question is whether this is actually the fault of technology, or the fault of capitalism.

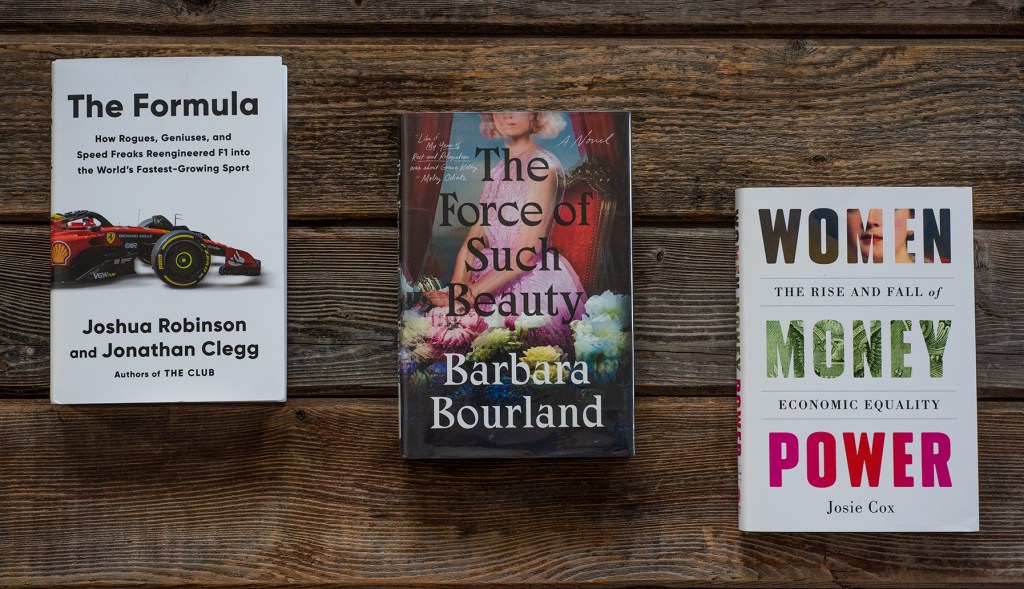

The Formula, Joshua Robinson and Jonathan Clegg

Are you one of the millions of newly-minted Formula One fans, thanks to Drive to Survive? Even if “lights out” or “box, box” or “Abu Dhabi 2021” mean nothing to you, you might well love The Formula. The authors, both WSJ sports journalists, clarify that this isn’t a detailed history of the sport exactly, more of a collection of stories, anecdotes and insights from the business and management side – and these tidbits do a terrific job of detailing F1’s exploding popularity worldwide. F1, loved in Europe for decades but only now building its fan base in the U.S., is an utterly fascinating sport with a collection of colorful characters engaging in complex rule changes, under-the-table agreements, coarse language, minute technical adjustments and blatant cheating. If you love scandal and appallingly inept “criminals,” the McLaren-Ferrari copy shop story alone is worth the price of admission.

The Formula does contain a number of curious factual errors, including Valtteri Bottas’ birth country (he’s Finnish, not Estonian) and the statement that no driver has died in a F1 race since Senna in 1994 (Bianchi didn’t technically die during a race but he did in fact die from an on-track incident). These seemingly simple yet blindingly obvious mistakes lead a reader to question what else might be inaccurate in the book. It’s a minor quibble but reasonable in the context of a non-fiction book about a wildly popular sport, written by top journalists who presumably had access to top fact-checkers.

The Formula does an excellent job of explaining F1’s unique position as possibly the world’s first post-modern sport: there are millions of people worldwide who consider themselves fans, can name every driver, every team and every livery set – but who have never watched an entire F1 race start to finish. This sport’s challenge will be in keeping those same eyeballs engaged with all its content channels, whether or not people watch the actual race. As another reviewer wrote, “This may not be a great book, but it is a great book about Formula One.” Errors aside, this is a quick, easy and entertaining read and perfect for recent fans and diehard Schumacher-era gearheads alike.

The Force of Such Beauty, Barbara Bourland

A terrific under-the-radar book club choice – it’s surprising that this book didn’t earn a larger press campaign. The Force of Such Beauty is a fairy tale, but perhaps not the kind of traditional fairy tale you might expect. A South African athlete marries a European prince and moves into a castle and they live happily ever after. Or do they? It’s easy to find thinly-veiled references to modern princess stories in this dark, compelling, propulsive novel, but the honest truth is that most of us are utterly fascinated by royalty, whether we’re willing to admit it or not, and The Force of Such Beauty makes the most of that unsettling fascination. The pacing isn’t perfect, some characters could be better developed and it could probably be shortened by about fifty pages, but The Force of Such Beauty will likely stay with you for some time – especially the ending. Don’t skip the author’s note at the end.

Women Money Power, Josie Cox

The Venn diagram where economic history, financial literacy and feminism overlap would be my very favorite non-fiction subject – if it really existed. There are relatively few books connecting women and money; considering that in the U.S., we were only allowed to open a bank account in our own name in 1974, and obtain a business loan without a male co-signer in 1988, this isn’t exactly surprising. Women Money Power is an enlightening, informative and engaging read, with a great deal of historical detail, but its subject matter renders it simultaneously fascinating and infuriating. On one hand, we’ve come so far in just a few decades – but we are now actively reversing many of our gains, and the aftermath of the pandemic will neatly undo the rest for us. From the intractable wage gap (currently 84 cents to the dollar) to the total lack of an educational system that supports working women and the obvious impossibility of affordable, accessible child care, to the fact that “women are never the right age,” it’s difficult to feel optimistic about our current place in the world. That said, this book is thorough, detailed, well-researched and a worthwhile read, primarily to learn about the women who broke trail before us and to inspire all women to take responsibility for their own financial security in order to be the change we want to see in the world.

As always, we’d love to hear what you’ve read this summer. Please share in the comments! Hoping you are safe and not breathing smoky air, wherever you might be.

Frostbite by Nicola Twilley

LikeLike

Thanks, Ann! I’ve requested this from the library.

LikeLike

Hurray for library access and physical books as well as digital ones. This book has no pictures or photos so the digital or audio versions will work as well as the print version. I am salivating, thinking Bout your home grown produce and commiserating with your grasshopper invasion this year. Hungry deer who eat everything, literally everything make it hard to grow food in my yard here in Michigan. Hurray for farmers’ markets.

LikeLike

Ann, we definitely have deer pressure here too – and a nine-foot game fence for exactly that reason. And a thousand times yes to both libraries and farmers’ markets! Wishing you all the best.

LikeLike