What are you reading lately? Sci-fi with aliens and vampires? Escapist fiction? Historical romance? Deep-thinking non-fiction? Any reading at all that prevents one from repeatedly googling, “Is the world ending?” fits the bill for me these days. Would love to hear what you’re immersed in, dear friends!

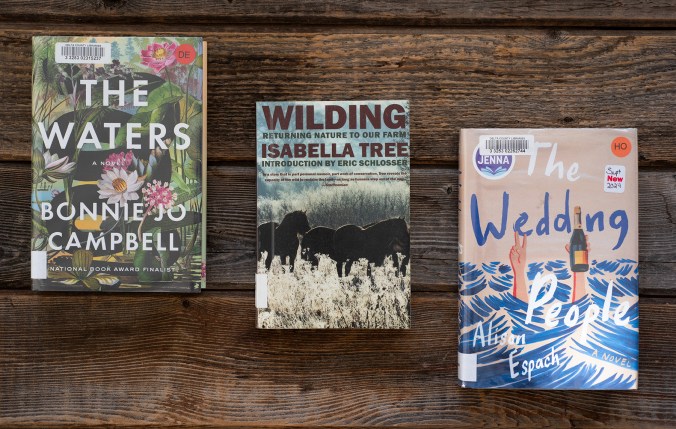

The Waters, Bonnie Jo Campbell

The Waters is a haunting, elegiac tale of the inexorable violence angry men visit upon women, the consequences women are forced to accept and how generational poverty and trauma and loss of connection from the land create cycles of despair. It’s also about the fiercest, toughest 11-year-old you’re likely to meet, the youngest in a lineage of skilled female healers and herbalists. Add to that a rich, fecund swamp setting plus gorgeous, powerful imagery of rattlesnakes and willow trees and ghosts and tumbledown island cottages and you’ve got a Midwest gothic tale that will grab you by the throat. Get someone else to read it too, because you’ll want to talk about this one.

Wilding, Isabella Tree

One of my favorite non-fiction reads of 2024, Wilding tells the two-decade story of a parcel of farmland in southwestern England pulled out of conventional farming just before bankruptcy takes hold and carefully encouraged to ‘rewild.’ After years of effort, including numerous missteps, maddening bureaucratic heel-dragging and mountains of paperwork, Knepp Estate is now one of Europe’s best examples of a successful rewilding project. It’s also a thriving ‘safari park,’ with ecology tours, a restaurant, farmstays and much more, and it must be noted that this is very much an aristocratic story with a good deal of landed gentry yomping around gazing moonily at nearly-extinct butterflies. The tale works because Tree’s writing is simply luminous; her vivid descriptions of birds, insects and other wild creatures bring the land to life. While the farm discussed here, in a lush, damp, temperate maritime climate, couldn’t actually be more different from our own high-plains desert farm environment, Knepp Estate is a shining example that land can thrive without necessarily doing things the way we’ve always done them. Truthfully, we’re going to need a lot more unconventional thinking like this in order to survive what’s coming.

The Wedding People, Alison Espach

After her divorce, Phoebe decides to end her life at a luxury hotel in Newport. Her plans are foiled, however, when she finds herself in the middle of the wedding-to-end-all-weddings. Hilarity, of course, ensues, as do miscommunications, confusing plot points, and total implausibility. I loved Phoebe’s midlife crisis, that point most (all?) of us reach where we finally realize that the hopes and dreams we had in our 20s maybe aren’t going to turn out exactly as planned. I also really enjoyed the dark humor of this book; there are some excellent laugh-out-loud moments. The male characters are thinly drawn and mostly just a bunch of self-centered cads, and the ending is a bit too fairytale, but The Wedding People tackles some hard, relatable topics with grace and empathy. This is by no means a perfect book, but it is worth reading.

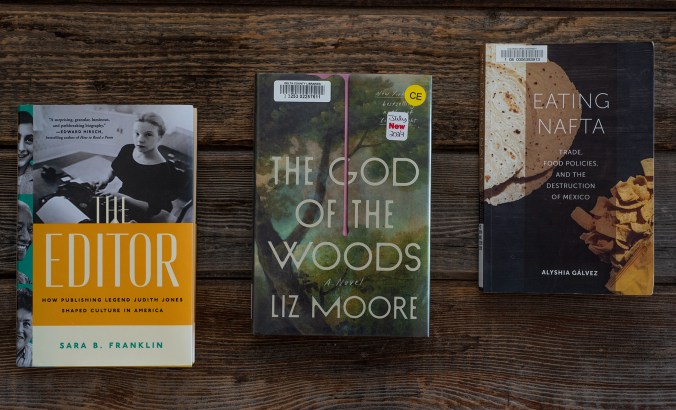

The Editor, Sara B. Franklin

The Editor is Sara B. Franklin’s posthumous valentine to Judith Jones, the legendary Knopf editor who brought the world Anne Frank, Julia Child, Anne Tyler, Edna Lewis and many more. After working with Jones on an oral history project in 2013 and becoming friends, Franklin was given unlimited access to Jones’s papers after her death in 2018; The Editor is the result. The book is detailed and thorough, even at a brisk 218 pages, and understandably focuses almost exclusively on Jones’s progression through an industry notoriously hostile to women and her staggering influence on cookbook publishing as we know it today. I wish that The Editor had gone into a bit more detail about Jones’s personal life, including her adoption and subsequent raising of a family friend’s two teenage children; at the same time, it is clear that Jones herself was a notoriously private person and she likely wouldn’t have given approval for this intimate look at her life, so wanting the book to delve deeper feels somewhat voyeuristic and grimy. Franklin obviously loved Jones and wants to show her best side; this lack of impartiality might have created a less-than-honest portrait of the subject. Nevertheless, Jones’s impact on publishing in general and cookbooks specifically cannot be overstated but has been mostly overlooked, and The Editor makes a valiant attempt at righting that wrong. Well worth a read for food and cookbook historians; also recommended is Jones’s own The Tenth Muse: My Life in Food.

The God of the Woods, Liz Moore

On its surface, The God of the Woods is merely a grocery-store mystery about a boy who goes missing in the Adirondacks, and his sister who also goes missing in the same woods some years later. Considered on a deeper level, however, this is a book about privilege, class, gender roles, societal expectations, second-wave feminism and much more, deftly woven into a sharp and tightly-crafted narrative. The author does an excellent job with the mid-seventies timeframe (with flashbacks to earlier years); the cast of characters is extensive, but each is carefully constructed and believable. There are some small quibbles in terms of plausibility, but the story’s overall strength more than compensates for minor plot weaknesses. The God of the Woods is nearly five hundred pages, but don’t let that deter you – it reads quickly and you’ll want to devour it to find out how all the puzzle pieces come together. I absolutely loved this book’s ending – one of the most satisfying finishes I can remember in recent fiction. Highly recommended.

Eating NAFTA: Trade, Food Policies and the Destruction of Mexico, Alyshia Galvez

“In 1991, there was only one Wal-Mart in Mexico. By 2012, there were over 2,000.” This data point neatly summarizes how the post-colonial expansion of American retail, coupled with exceedingly one-sided governmental policies like the North American Free Trade Agreement, have fundamentally altered Mexico’s diet, economy and culture – and not to the benefit of the Mexican people. Galvez thoroughly explores NAFTA’s complicated origins and its impact on the traditional Mexican diet, and also addresses the massive effect NAFTA had on immigration. Trade negotiators expected displacement of 500,000 rural people; the real number was twenty times that – a decade after NAFTA went into effect, ten percent of the Mexican population resided in the U.S. This is not an insignificant figure, especially considering the current mood around immigration, and it is essential that we acknowledge our own role is creating this catastrophe. In addition to displacing rural people, U.S. policies also destroyed traditional agriculture (specifically corn), making Mexico one of the least-healthy countries in the world, with some of the highest consumption rates of sugary drinks and processed foods. Eating NAFTA is a well-written and thoroughly researched book that convinces the reader to ignore all the rhetoric about how the U.S. has “suffered so terribly” under trade agreements. When one of the players at any negotiating table is an 800-lb. gorilla like the U.S., it is highly unlikely that we’ll be dealt a losing hand – particularly when we hold all the cards.

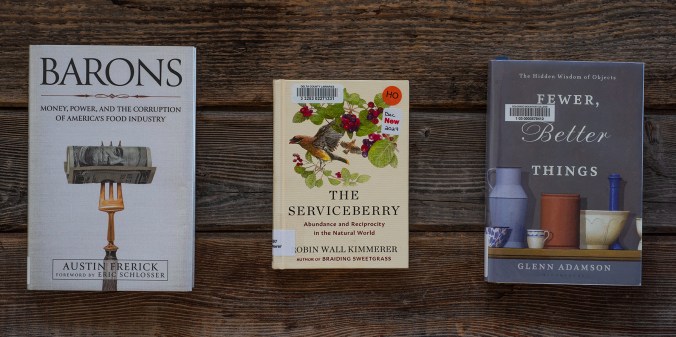

Barons: Money, Power and the Corruption of America’s Food Industry, Austin Frerick

“That’s why concentration of economic power has long been closely associated with a rise in extremist politics. Authoritarians prey on people who see their communities crumbling and feel that they are losing power over their lives and their financial future. But one of the great paradoxes of authoritarians is that they’re most often closely aligned with the same powerful interests causing this state of affairs…it not a coincidence that as economic balance is disappearing, political balance is fading with it. “

If you’re looking for a reasonably quick overview of America’s deeply corrupt food and agricultural system, look no further than Barons. Austin Frerick smartly divides the book into seven profiles of various industry “barons,” including brands you’ll certainly know and others who intentionally remain hidden in the shadows. If you’ve read any number of books on food politics you’ll be shocked but likely won’t be surprised, but if you eat commodity meat and/or are planning a move to bucolic Iowa, I highly recommend you read this. The most depressing aspect of this well-researched book is that it is almost impossible for Americans to extricate themselves from an ag/food system elegantly designed to break all the rules and suffer no consequences – although based on our country’s eating habits, we’re apparently pretty content with things, just so long as the price of eggs doesn’t go up. And if that happens (ignoring that we pay less for food than any other developed nation), we’ll just vote in an oligarchy virtually guaranteed to make things far, far worse.

The Serviceberry, Robin Wall Kimmerer

“When an economic system actively destroys what we love, isn’t it time for a different system?”

This slender volume, an expansion on a long-form magazine piece, is a worthwhile follow-up to Kimmerer’s best selling Braiding Sweetgrass. The subtitle, “Abundance and Reciprocity in the Natural World,” clearly shows the essay’s focus – that despite what the overlords would have us believe, there is, in fact, enough for everyone out there – if only we didn’t take so much and then hoard what we take. Kimmerer proposes establishing community ties and embracing a gift economy, both within human networks and the natural world, as an antidote to the global destruction and vicious polarization we’re all now part of. The solution might sound simplistic, but solutions don’t always need to be complicated to work. A quick read and highly recommended.

Fewer, Better Things, Glenn Adamson

“Stop adding things to our lives…attend to the things that are already there, and above all, find meaningful ways to connect to each other.”

I’ve been reading a lot on craft and the art of handwork lately, specifically why we’re still drawn to making things by hand when obviously the robots/children/slaves can do it cheaper/faster/more consistently. But we have opposable thumbs for a reason, and surprise! It’s not actually for swiping or scrolling! It’s because we’ve evolved to learn from our immediate environment and to make things, from cave wall paintings to a chair to Notre-Dame. When our first playthings are now bottomless black mirrors training us to consume, rather than wooden blocks we can manipulate and learn from, we lose our material intelligence, “a deep understanding of the material world around us, an ability to read that material environment, and the know-how required to give it new form. This skill set was once nearly universal in the human population, but it has gradually shifted to specialists.” We’re squandering a once-nearly-universal human trait and delegating it to specialists! This is not progress – this is de-evolution and it’s clearly not working in our favor (we’re now also losing our innate navigation skills thanks to ubiquitous map apps). In this beautifully written book, Adamson, a museum curator, argues a strong case that we’ll need to work even harder on having ‘fewer better things’ if we want to save our planet and ourselves.

This book round-up has an interesting thread of destruction, violence, redemption and connection running through it! Here’s hoping you, too, are peacefully lost in worlds other than our own, while still thinking about what we each can do to improve the world we’re in.

I love reading your book reviews. I just finished “This is Why You Dream” which I found fascinating but very science heavy. Also finished “State of Wonder” which was fantastic. Loved God of the Woods as well! Thanks for all the recommendations!

LikeLike

Thanks, Sara! The dreaming book sounds really interesting, and Ann Patchett is an absolutely brilliant writer. I love hearing about what other people are reading!

LikeLike