The corral’s warm metal panel is covered with grasshoppers each morning.

Friends, hello. Muted greetings from high summer in the desert, where it is hot, smoky and dry. Let’s not mince words – the world is full of terrible suffering right now, most of it instigated and/or supported by the current regime. It is hard to know how to phrase things appropriately in the face of an entirely intentional famine. We are experiencing our worst farming season in eight years, yet we have easy access to whatever food we might need or want – but children are being purposefully, deliberately starved, and collectively we are obviously fine with this. We are also fine with concentration camps, a militarized police state and taking benefits from poor kids to enrich billionaires. The active cognitive dissonance required to manage one’s daily existence in 2025 frequently leaves me in despair.

A lettuce plant and marigolds, both stripped to the stalks in a few hours.

Here’s one thing I do know – along with cruel, vengeful, power-hungry leaders, grasshoppers (and locusts) can also cause famine. The thousand-year drought in the American Southwest has created ideal conditions for these hardy creatures to thrive, and they are most certainly thriving here. Just about every conversation we’ve had with local friends over the past two months has centered on two topics: grasshoppers and drought. We’ve had no appreciable moisture this year, and the grasshoppers have absolutely annihilated many of our crops. Unless you have the experience of walking amongst our raised beds or our pasture and seeing tens of thousands of insects move at once, unless you’ve been hit in the face and arms repeatedly by these sturdy bugs, unless you’ve seen firsthand the scale of the devastation – you cannot possibly appreciate how bad things are here this year.

The kale is not thriving.

The brassicas (kale, cabbages, broccoli, bok choy, and so on) have taken the most damage, by far. Entire beds are destroyed in a few hours or days. I am pulling all the broccoli plants this week as they’re so badly eaten that there is virtually no chance they’ll develop proper heads this season, and it’s just painful to look at them every day. Mint, basil, thyme, tarragon – all the soft herbs are gone entirely.

The bean yield will sadly be far lower than expected this year.

As with all crops, the bean plants are at their most vulnerable when they’ve just put on their first true leaves; the grasshoppers love these tender, nutrient-packed starts. The rows are littered with empty stalks that didn’t survive, but we are seeing some resilience from beans that managed to escape that initial onslaught. We’ll likely get some beans, but certainly not the amount we’d planned on.

Dark-spotted blister beetles, a new arrival for us this year.

An enemy, but also an ally. It’s a delicate balance.

Because Nature never makes mistakes, the grasshopper invasion has been followed by dark-spotted blister beetles, who feast upon grasshopper larvae. We’d never seen these before, but they certainly have plenty to eat this year – although they also took out the beet and chard leaves on their way. They love alfalfa, too, and can be toxic to horses if their poison is heavily concentrated in hay bales.

Tassels on Painted Mountain corn; it’s drought-tolerant, cold-tolerant and apparently grasshopper-tolerant.

On the plus side, the grasshoppers have thus far done very little damage to our ‘Painted Mountain’ corn, an heirloom that I am exceptionally proud to grow this year. (You can see a little exploratory leaf-chewing in the photo above, but overall devastation is minimal.) I am so hopeful for this stand of open-pollinated flour corn and will share an update when we harvest.

The tomatoes and peppers have also mostly survived, with the exception of a few replacement transplants that disappeared in hours. I suspect the bitter compounds in well-developed Solanaceae plants aren’t appealing to grasshoppers, though the tiny ones don’t put up much of a fight since they’re likely too little to have developed their defenses. This metaphor is not just relevant in farming, obviously.

Lettuce plants reproduce by sending out their light seeds on the wind.

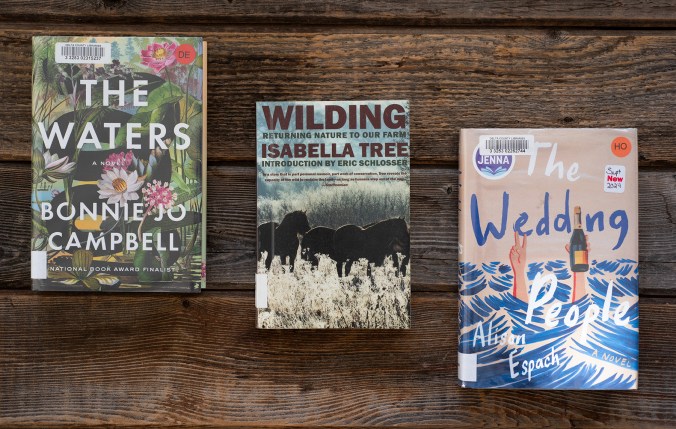

And of course the lettuce has gone to seed by now, so it’s time to harvest the little fluffy puffs to collect seeds for future plantings. Saving seeds always reminds me that gardening and farming are ultimately acts of optimism and hope, both of which I am sorely lacking at the moment.

Much as I wish I had a more positive update to share, I am also unwilling to pretend that farming is always easy or fun or rewarding. Sometimes it’s a miserable, exhausting sunbaked slog while watching plants be devoured in a matter of hours. Sometimes it’s replanting precious beans two and three times in the hopes they’ll survive the initial attack. Sometimes it’s bursting into helpless, infuriated tears, because when you’re irrigating, no one can hear you cry. And sometimes it’s taking resigned solace in the famous Zora Neale Hurston quote, “There are years that ask questions and years that answer.” This is a year for questioning, dear friends, and for questioning a lot more than just farming.

Thanks for being here, as ever.