“I don’t know about you, but I am decidedly not bounding into 2026.” I read more books this year than I have in any single year previously, which tells you so much about a) my desperate attempts to find relief from the news and b) my desperate attempts to find relief from our worst growing season ever. The upside, of course, is that I read some truly terrific books (and some truly terrible ones, too). This review post is heavy on the non-fiction, but I cast a wide net this year – poetry, cookbooks, memoir, biography and more. What an immutable joy, to still have so many wondrous books to read when all feels lost.

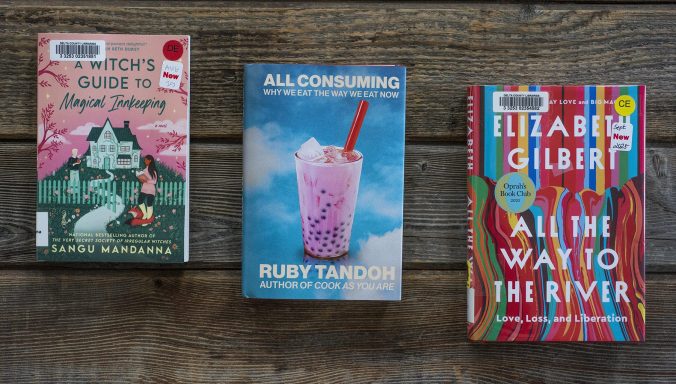

The Witch’s Guide to Magical Innkeeping, Sangu Mandanna

This quirky oddball of a book appeared again and again in the “must read” recommendations of many different newsletters I love. And so it is that I suggest it as a must-read, too, because it’s everything you need right now – misguided magic, an unusual house, an incredible cast of disparate characters – and it’s so much more than all of that. It’s repeatedly been described as “charming,” which is of course true, but it’s also just like sinking into a warm bath. A lovely read.

All Consuming, Ruby Tandoh

Truthfully, I am not at all the target audience for this book, as I am not Terminally Online and have little-to-no knowledge of the vicissitudes of social media. (I am instead very much a product of the Condé Nast print journalism heyday and still an avid subscriber of print magazines, what few useful ones remain.) All Consuming doesn’t seem to have a theme or a plan, exactly, which suits the messy, vague topic of ‘food culture’ just fine. Tandoh, a former model, reality-show contestant, and cookbook author, is an engaging writer and clearly knows that of which she speaks, and I enjoyed the mix of large-scale cultural commentary interspersed with personal anecdotes. That said, she walks a razor’s edge of appeal with the perpetual use of Internet slang; this will not only date the book rather quickly, but might also serve to alienate and isolate readers who would otherwise be interested in the subject matter but feel lost in the hyper-specific of-the-minute language. Also, many of the social media personalities mentioned are unlikely to be remembered even a few months from now, further dating the book, and All Consuming careens wildly back and forth between the U.S. and U.K. food worlds, muddying the throughline. There’s much to enjoy here for folks interested in food culture and perhaps if you were raised on The Algorithm from birth you wouldn’t find this book particularly jarring, but as Kim Severson wrote in her NYT review, “Today, food culture is a churning, untamed river, delivered by an algorithm designed to simultaneously render you hungry, jealous and terrified.” For those of us who grew up paging blithely through old copies of Gourmet, these are dark times indeed.

All the Way to the River, Elizabeth Gilbert

Released in September to great fanfare, a massive publicity campaign and more than one scathing review, All the Way to the River is Elizabeth Gilbert’s latest memoir, a story of her doomed co-dependent relationship with her partner Rayya, a drug and alcohol addict who died of pancreatic cancer. Gilbert is a tough author to review – her books will sell millions of copies, no matter the critical response, but I’m not the only reader who felt the self-help guru role wore a little thin with this latest memoir. Gilbert can seriously write – there is no doubt of that – and the book contains some stunning, and devastating, passages about caregiving and grief and loss. It also, however, contains conversations with both “God” and her dead partner (who oddly provide exactly the answers she wants to hear), twinkly Instatherapy adages, childish drawings and poetic interludes. The relationship detailed in the book is dark, messy and intense, with self-destructive addicts dragging each other into ever-worsening spirals; All the Way to the River could have been a notable entry into the addiction memoir genre if Gilbert had simply stuck to the plot, but it veered off wildly into self-help and inner children and ostensible redemption and left me feeling vaguely sordid and sad and voyeuristic. I couldn’t shake the feeling that publishing this story essentially paid for the financial ruin mentioned. Not recommended, but if you read it and have a different view, I’d love to hear.

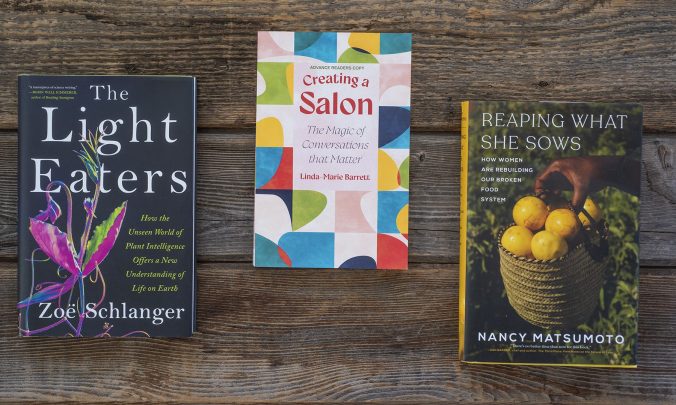

The Light Eaters, Zoë Schlanger

The Light Eaters is a perfect example of what kind of stunning book might result when a journalist starts looking around for other options – and develops a previously-unknown obsession with plants. Schlanger has covered climate change for more than a decade, but burnout came on hard and strong a few years ago. “It’s bleak out there,”’ she says of covering climate change, “and I started looking around for something else to cover — something else in the sciences that publication would be interested in, but that would also give me the sense of vitality and awe — these experiences that we can have with the natural sciences when they are wondrous.” Wonder is exactly what you’ll feel while reading this; if you’re not already in love with Plantae – they eat light, for goodness’ sake! – you’re guaranteed to be hopelessly head-over-heels after finishing The Light Eaters. There is still so much to feel bleak about, especially where endangered species are concerned, but when you learn about what incredible things plants do to survive and thrive and reproduce, and the dogged, brilliant scientists working to save them, you’ll never look at plants or the natural world the same way again. This is the kind of book that allows for a spark of hope, and the kind of book that encourages young people to pursue science. Highly recommended.

Creating a Salon, Linda-Marie Barrett

One of my key 2025 goals was to build and expand my immediate community; a year later, I can confidently say that I was remarkably successful in these efforts and my life is immeasurably enriched by the varied relationships I’ve established. I love reading about ways to be an “artful gatherer” (see also: Priya Parker’s Group Life) and how I can do a better job as a teacher, a leader and a guest…and I have a not-so-secret desire to have a salon (the old meaning, not a place for hairstyling) of my own, where a group of smart, thoughtful, opinionated women come together to discuss and debate thorny, delicate issues. I particularly liked the parts of this book that addressed the essential aspects of mutual respect and emotional safety within a group framework; this year I’ve struggled with a couple of exceedingly difficult interactions within gatherings, and I want to learn how to handle these challenging situations with grace and respect, and also to know sooner when someone is destroying a group dynamic and how to move forward from that. I loved Creating a Salon and the examples and tips offered; while a true salon is probably not in my immediate future, our collective social skills remain rusty post-pandemic and there’s a lot we can all learn from this warm, lovely book.

Reaping What She Sows, Nancy Matsumoto

This book’s subtitle is “How Women Are Rebuilding Our Broken Food System,” but that statement just simply isn’t true. Our food system is definitely broken, but it is definitely not being rebuilt, most certainly not in 2026 America. Reaping What She Sows offers detailed profiles of female farmers, fishers, vintners, butchers, cacao entrepreneurs and more; while these stories are vaguely inspirational, they also point to premium food and drink offered in tiny geographical niches and wildly out of financial reach for almost all Americans – not a solution to our broken food system and wholly inaccessible to most of us. The brutal truth is that while Americans claim to want a better food system, we will always instead vote for a mad king who promises to lower the price of eggs on Day One, even if said king has zero control over the price of eggs. We still spend a smaller share of our income on food than any other developed country, yet we are so accustomed to cheap, mass-produced corn, soy and meat that it never occurs to us how much we’re actually paying in externalized costs for health care, environmental destruction and human-rights abuses. We want cheap shrimp and a lot of it and that’s really the whole story. I’d love to believe the inspirational platitudes and heartwarming tales of hard work and old-fashioned values put forth here and in many other similar books, but I’ve spent too much time in the food and ag industries to see any meaningful change on the near horizon, plus we still have to reconstruct everything that gets burned down during this regime. Additionally, this book suffered from critical editing, proofreading and continuity errors, which diminished my limited enjoyment even further. Not recommended.

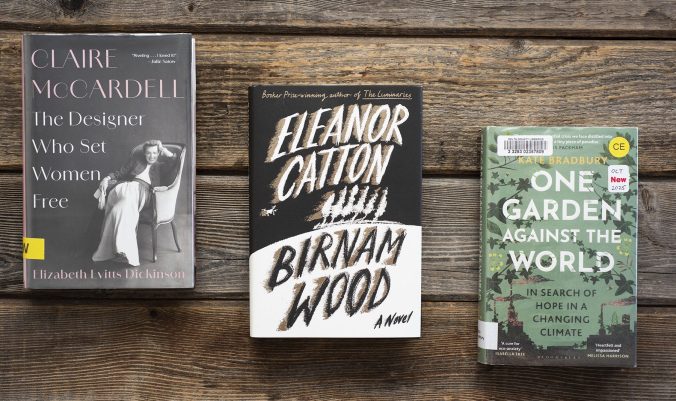

Claire McCardell: The Designer Who Set Women Free, Elizabeth Evitts Dickinson

A personal favorite genre: Books About Incredible Women Who Were Hugely Influential But Who Have Mostly Been Forgotten or Ignored by History. Claire McCardell fits this highly-specific genre perfectly, and this was my favorite biography of the year. Exquisitely written and so richly detailed, this gorgeous book tells the story of the designer who brought us hoodies, denim, pockets (‘women shouldn’t have pockets because they might hide things in them’) and more, but whose name and legacy have mostly been forgotten. In reading this wonderful book, I learned that while vintage pieces in decent to good condition can be found for most notable designers of the twentieth century, it is almost impossible to find an original Claire McCardell in any condition – because these clothes were so practical and so fashionable that women wore them until they fell apart. What an incredible legacy! I especially love when the reader can see how much work went into crafting a book; Evitts Dickinson’s writing and research are truly exceptional. Claire McCardell was an icon in all respects, and her contributions to American fashion and design have been grievously ignored. This stellar biography attempts to right that wrong. Highly recommended, for fans of fashion, design and women’s history.

Birnam Wood, Eleanor Catton

My favorite fiction of the year was Charlotte McConaghy’s Wild Dark Shore, but Birnam Wood was a close second. The book was released in 2023 but somehow feels even more relevant given the head-spinning events of the past year. Birnam Wood is not for everyone – the prose is dense, murky and philosophical – but if you’re curious about what happens when a guerrilla gardening collective goes up against a tech billionaire in remote New Zealand, this book might be just what you didn’t know you needed. Many reviews mentioned the book’s close resemblance to a Shakespearean tragedy (“Macbeth shall never vanquished be until Great Birnam Wood to high Dunsinane Hill…”) and the spectacular ending revels in these literary genetics. Part eco-thriller, part treatise on Big Tech and its ever-expanding tentacles, Birnam Wood definitely leaves the reader with plenty to mull over. Highly recommended, if you’re into collectivism, incredibly caustic anti-capitalist rants and poor decision-making skills.

One Garden Against the World, Kate Bradbury

A cover quote on One Garden Against the World from Isabella Tree (I read her book Wilding earlier this year and loved it) reads “A cure for eco-anxiety.” This couldn’t be further from the truth, in my opinion; the climate anxiety was so shriekingly high in this book that I felt like I was reading my own journal – not a pleasant experience. Bradbury clearly has an incredible wealth of knowledge about the natural world – her plant ID skills are staggering – but she also presents herself as the only person who cares about any of the destruction we’re wreaking, even while discussing the network of friends and neighbors who help and support her work. One Garden Against the World caused me a great deal of stress, simply because it read so terrifyingly close to my own panic, but I do know that screaming, haranguing and shaming will accomplish precisely nothing. Given the tone, I’m surprised this book was published; to read it, you’d think we might as well give up now. There is no possible way we can make any impact on the climate crisis if everyone thinks that all hope is already lost; it’s imperative that folks realize that small, individual actions do add up to a sum greater than the parts, plus we have to collectively pressure governments and corporations to shoulder their fair share. A challenging read; not recommended.

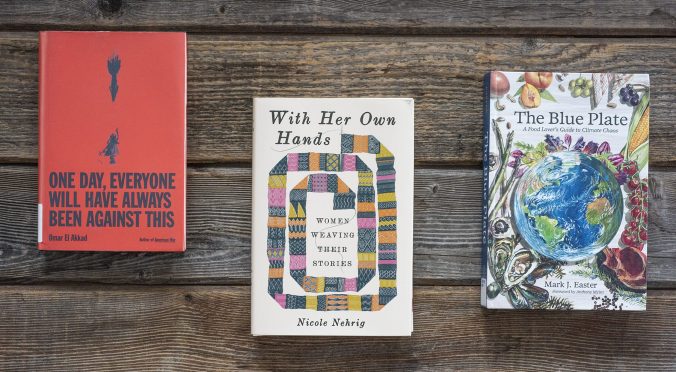

With Her Own Hands, Nicole Nehrig

For millennia, textile work, including weaving, dyeing, knitting, embroidery and much more – has been primarily made by women and therefore denigrated as ‘women’s work.’ While many of these textiles were purposeful, for clothing, warmth and shelter, plenty more were crafted as art, as activism, as a way of processing emotions and as a way of allowing women to be heard, even when their voices were regularly silenced. With Her Own Hands follows disparate textile cultures across centuries and across the world, and deftly shows how these threads have both literally and figuratively tied women together. The book touches briefly on textiles used in protest and activism as well as the sudden spotlight glare of popularity thrust upon women like the Gee’s Bend Quilters, whose works now regularly sell for thousands of dollars and whose success has been both beneficial and jarring, in perhaps equal measure. With Her Own Hands is deeply researched and well-written; Nehrig is clearly a textile artist herself and her love of craft shines through. My only small complaint about the book is that I would have perhaps liked more critical examination of modern textile production, especially as reflected in the fast-fashion production churn in countries such as Bangladesh. I do appreciate that difficult topic could fill many books on its own but I think it’s important to acknowledge the large gap between “textile hobby craft” now, practiced by mostly wealthy Western women for relaxation and enjoyment, and the often-miserable conditions endured by low-income women of color producing our incredibly cheap and disposable tank tops, blankets and jeans. Beyond that, I thoroughly enjoyed With Her Own Hands and highly recommend it for anyone interested in textiles and women’s history.

The Blue Plate, Mark J. Easter

It is my own fault that I am so magnetically drawn to books at the intersection of food, farming and the climate crisis; they are obviously such catnip to me, even though they’re regularly disappointing. While The Blue Plate is marginally better than Reaping What She Sows, it’s again the same tired story: eat less (or no) meat and seafood (unless it’s oysters or mussels); what meat and seafood you do eat should be ‘sustainable’ and grievously expensive. Don’t waste food, and compost what you do waste. Stop eating out-of-season. Everything should be organic, of course. It’s all so trite and predictable and choir-preaching and it’s also totally pointless, because it’s aimed primarily at wealthy white Westerners who are already generating far more than their per-capita share of carbon, and who for the most part love grilled rib-eyes and wouldn’t be caught dead with a compost pile in their manicured suburban backyard of Round-Up perfect bluegrass. While I loved the Colorado people and places that appeared in The Blue Plate, it’s overall painfully homogeneous and offers virtually no diversity in terms of the “menu” nor the folks profiled; my biggest issue, however, is that books like these are only read by people who already know all of this and are still unwilling to make necessary lifestyle changes. (And yet I keep reading these books, so I am absolutely part of the problem too.)

One Day, Everyone Will Always Have Been Against This, Omar El Akkad

Forgive this appearing out of order against the image above, but this review post must finish on this particular book. I can’t phrase this review any better than Nic Antoinette: “This year, more than ever, I have been intensely drawn toward writing that has at its foundation an unabashed moral clarity, such as One Day, Everyone Will Have Always Been Against This, by Omar El Akkad. Absolutely the most impactful book I’ve read all year.” I echo this. A lot has shifted in my own values and beliefs this year, and this was by far the best non-fiction book I read, too. I think it should be required reading for everyone in the Western world.

As ever, we hope you are warm and sheltered and have something delicious to eat. Share what you’re reading in the comments!

Thank you, Elizabeth, for this lovely review. I’m so glad you enjoyed Creating a Salon!

LikeLike

Hello Linda-Marie! Thank you for your kind comment, and for writing such an excellent book! I am decidedly envious of your salon experience and hope I can create that for myself one day! Warmest wishes to you and yours.

LikeLike